先来看来视频,打开一下思路,从UI设计师的角度看”什么是场景化思维”,视频来自非凡实验室:

NINEIDEA:接下来我们分析下工业设计的场景化设计,工业设计中的场景化设计是一种以用户为中心、以使用场景为核心的设计方法,强调将产品功能、用户需求与具体的使用环境(时间、空间、人物、行为、目的等)相结合,通过构建真实或模拟的使用场景,让产品设计场景思维更贴合用户在特定情境下的实际需求和情感体验,从而提升产品的实用性、易用性和情感价值。

核心内涵

- 以场景为纽带连接用户与产品

- 不再孤立地设计产品功能,而是考虑用户 “何时、何地、为何、如何使用产品”。例如,设计一款户外便携灯具时,需考虑用户在露营、徒步、夜间维修等不同场景下的光照强度、续航、便携性、防水性等需求差异。

- 关注多维需求

- 功能需求:产品在特定场景下的核心用途(如车载充电器需适应颠簸环境、手机支架需兼容不同车型)。

- 体验需求:用户在场景中的操作便捷性(如厨房小家电需考虑戴手套操作、潮湿环境下的按键反馈)。

- 情感需求:场景引发的心理感受(如儿童玩具需营造安全、趣味的互动场景,医疗设备需缓解用户的焦虑感)。

- 动态化、情境化的设计思维

- 考虑场景的变化性:同一用户在不同场景下的需求可能冲突(如通勤时需要轻便的笔记本电脑,办公时需要高性能配置),设计需平衡或适配多元场景。

- 挖掘隐性需求:通过场景分析发现用户未明确表达的需求(如雨天使用手机时,用户可能需要防水且单手操作便捷的手机壳)。

核心要素

- 用户画像:明确目标用户的身份、习惯、痛点(如老年用户、儿童、户外爱好者等)。

- 场景定义:拆解具体场景的五要素 ——时间(Time)、地点(Place)、人物(User)、行为(Action)、目的(Purpose)(即 TPUAP 模型)。

- 场景模拟:通过故事板、用户旅程图、场景剧本等工具,可视化用户在场景中的操作流程和体验触点。

- 迭代验证:通过原型测试或用户实测,在真实场景中检验设计是否符合预期(如在地铁场景测试折叠座椅的便携性,在会议室场景测试投影仪的无线连接效率)。

典型应用场景

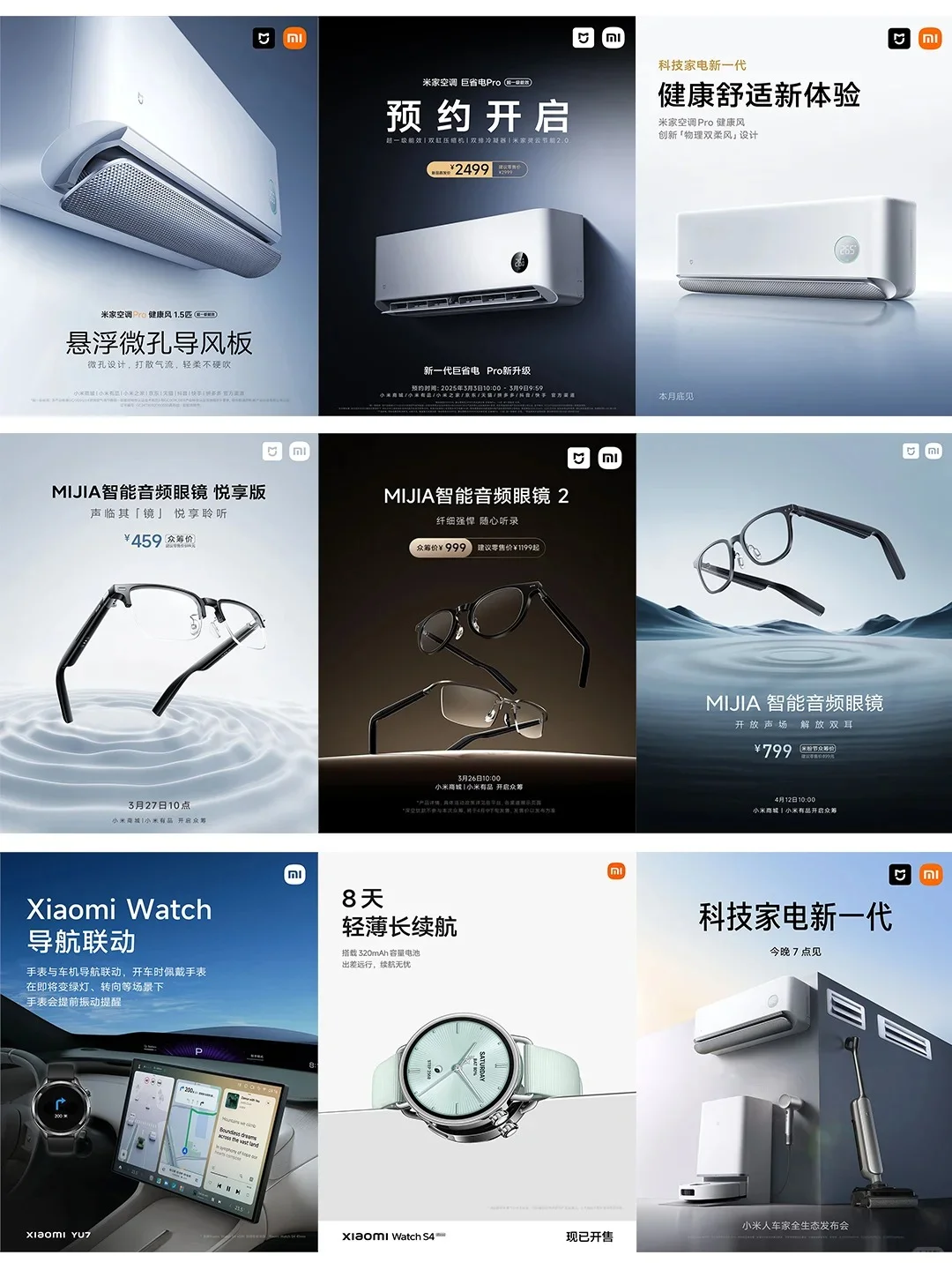

- 智能产品设计:如智能音箱在家庭场景中需兼顾客厅娱乐、卧室助眠、厨房提醒等功能,通过场景化设计实现多模式切换(如 “观影模式”“烹饪模式”)。

- 交通工具设计:汽车内饰设计需考虑驾驶场景(安全导向)、通勤场景(舒适性)、载人场景(空间灵活性),甚至自动驾驶时代的 “移动办公 / 休息场景”。

- 公共设施设计:公园座椅需结合 “晨练休息”“亲子互动”“阅读独处” 等场景,调整座椅高度、材质、遮阳 / 挡雨功能。

- 消费电子设计:手机外壳设计需考虑 “单手握持拍照”“口袋收纳”“车载固定” 等场景下的防滑、轻薄、接口适配性。

价值与意义

- 提升用户体验:让产品更 “懂” 用户在特定场景下的需求,减少使用障碍(如盲文按键在电梯场景中的应用)。

- 增强产品竞争力:通过差异化的场景适配(如针对 “宝妈通勤” 设计的多功能婴儿车),满足细分市场需求。

- 促进情感连接:场景化设计常融入文化、习惯或记忆元素(如复古收音机造型的蓝牙音箱,唤起用户对特定年代的情感共鸣)。

- 降低设计风险:提前规避场景中的潜在问题(如户外工具的防锈设计、浴室电器的漏电保护),提升产品可靠性。

与传统设计的区别

传统工业设计可能更聚焦产品本身的功能、形态或美学,而场景化设计则将产品视为 “场景中的角色”,强调产品与用户、环境、行为的动态互动。例如,传统水杯设计关注容量和材质,而场景化设计会进一步考虑 “运动时单手开合”“办公时防泼溅”“旅行时折叠收纳” 等具体场景下的细节优化。

场景化设计是工业设计从 “功能导向” 向 “体验导向” 升级的重要方法,通过 “代入场景、拆解需求、精准适配”,让产品不仅满足物理功能,更成为用户在特定生活片段中的 “得力助手” 或 “情感伙伴”。

NINEIDEA:Scenario based design in industrial design is a user centered and usage scenario centered design method that emphasizes the combination of product functionality, user needs, and specific usage environments (time, space, people, behavior, purpose, etc.). By constructing real or simulated usage scenarios, the design can better fit the actual needs and emotional experiences of users in specific contexts, thereby enhancing the practicality, usability, and emotional value of products.

Core Connotation

Using scenarios as a link to connect users and products

No longer designing product features in isolation, but considering when, where, why, and how users use the product. For example, when designing an outdoor portable lighting fixture, it is necessary to consider the differences in lighting intensity, battery life, portability, waterproofing, and other requirements of users in different scenarios such as camping, hiking, and nighttime maintenance.

Pay attention to multidimensional needs

Functional requirements: The core use of the product in specific scenarios (such as car chargers that need to adapt to bumpy environments, and phone holders that need to be compatible with different car models).

Experience requirements: User convenience in operating scenarios (such as wearing gloves to operate small kitchen appliances and providing button feedback in humid environments).

Emotional needs: psychological feelings triggered by the scene (such as children’s toys needing to create safe and fun interactive scenes, medical equipment needing to alleviate users’ anxiety).

Dynamic and contextualized design thinking

Consider the variability of scenarios: the needs of the same user may conflict in different scenarios (such as requiring a lightweight laptop for commuting or high-performance configuration for office work), and the design needs to balance or adapt to multiple scenarios.

Explore implicit needs: Through scenario analysis, identify user needs that have not been clearly expressed (such as when Rainangel uses a phone, users may need a waterproof and easy to operate one handed phone case).

Core Elements

User Profile: Clarify the identity, habits, and pain points of the target user (such as elderly users, children, outdoor enthusiasts, etc.).

Scenario definition: Decompose the five elements of a specific scenario – time, place, user, action, and purpose (i.e. TPUAP model).

Scenario simulation: Visualize the user’s operation process and experience touchpoints in the scenario through tools such as storyboards, user journey diagrams, and scenario scripts.

Iterative verification: Through prototype testing or user testing, verify whether the design meets expectations in real scenarios (such as testing the portability of folding seats in subway scenes, and testing the wireless connection efficiency of projectors in conference room scenes).

Typical application scenarios

Intelligent product design: For example, smart speakers need to balance functions such as entertainment in the living room, sleep aid in the bedroom, and kitchen reminders in home settings, and achieve multi-mode switching (such as “movie watching mode” and “cooking mode”) through scene based design.

Transportation design: The interior design of automobiles needs to consider driving scenarios (safety oriented), commuting scenarios (comfort), passenger scenarios (spatial flexibility), and even “mobile office/rest scenarios” in the era of autonomous driving.

Public facility design: Park seats need to be adjusted in height, material, and sun/rain blocking functions in conjunction with scenarios such as “morning exercise rest,” “parent-child interaction,” and “reading alone.

Consumer electronics design: The design of mobile phone cases should consider anti slip, lightweight, and interface compatibility in scenarios such as “one handed holding for photography”, “pocket storage”, and “car fixation”.

Value and Significance

Enhance user experience: make the product more “understand” the needs of users in specific scenarios, and reduce barriers to use (such as the application of braille buttons in elevator scenarios).

Enhance product competitiveness: Meet segmented market demands through differentiated scenario adaptation (such as multi-functional baby strollers designed for “mom commuting”).

Promoting emotional connection: Scene based design often incorporates cultural, habitual, or memory elements (such as retro radio shaped Bluetooth speakers that evoke emotional resonance with users for a specific era).

Reduce design risks: Avoid potential issues in the scenario in advance (such as rust prevention design for outdoor tools and leakage protection for bathroom appliances), and improve product reliability.

Difference from traditional design

Traditional industrial design may focus more on the functionality, form, or aesthetics of the product itself, while scenario based design regards the product as a “role in the scene,” emphasizing the dynamic interaction between the product and users, environment, and behavior. For example, traditional cup design focuses on capacity and material, while scenario based design further considers the optimization of details in specific scenarios such as “one handed opening and closing during exercise”, “splash prevention during office work”, and “folding and storage during travel”.

Scene based design is an important method for upgrading industrial design from a “function oriented” to an “experience oriented” approach. By “immersing in the scene, breaking down requirements, and accurately adapting”, products not only meet physical functions, but also become “capable assistants” or “emotional partners” for users in specific life segments.